“I feel that the moment, the rightness of the moment, even though it might not make sense in terms of its cause and effect, is very important.” -M.F.

“I feel that the moment, the rightness of the moment, even though it might not make sense in terms of its cause and effect, is very important.” -M.F.

By Max Mandel, violist in The Knights

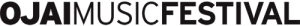

I find it difficult to talk about Morton Feldman. I’m in awe of his output. I find his music to be exquisitely beautiful and intellectually challenging, a combination very few composers achieve. I often find myself saying to my colleagues, “Yup, another great piece by Feldman.” You start thinking about him and he becomes larger and larger in your mind and at a certain point he becomes too big to deal with. It’s well-known how huge he was. 6 feet, almost 300 pounds. The thick mop of greasy black hair, the coke bottle glasses. The massive appetite, intellectual and sensual, hungry for life. The endless words, the words that poured out of him, the constant conversations with everyone (although he admitted to an interviewer once, “The problem now is that all these things are evasive subterfuges from sitting down and writing that piece of music.”).

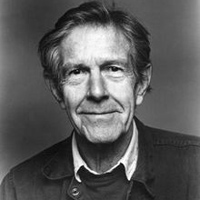

He was engaged in a lifelong debate with the musical giants of his time: Boulez, Cage, Stockhausen. After you’re captured by his music, the legend of the man becomes almost even more captivating. For me there is a ghoulish danger there. A strange thing about living in New York City is this continual pull of the legends and the ghosts that live here. I was standing at the corner of 72nd and Central Park West when some tourists haltingly inquired, “Excuse…could you please show where the Beatle was…” they trailed off in embarrassment and yeah, they should be embarrassed, a human being was murdered right there. I shook my fist at them after pointing them in the right direction because I recognized myself in their faces.

John Cage lived for a time in a building at 326 Monroe Street (since demolished) almost underneath the Williamsburg Bridge. Morton Feldman joined him for a year. Christian Wolff, David Tudor, and Merce Cunningham were always there. There isn’t a comparable place in recent music history. You could take Vienna with Haydn and Mozart, Schubert and Beethoven and Louis Spohr, running around in the same streets but imagine if they were closer together in age and hung out at Haydn’s place all the time! There’s nothing like it. I’ve spent a lot of time with Feldman’s scores and writings, wanting to get closer and closer to him. I’m lucky enough to play in a string quartet with three other guys who share my obsession (and we’ve got some serious Feldman-heads in The Knights too) and we’re always tickled by new things we find in his music. The little winks at the performer, the tiny, almost imperceptible changes that happen when he repeats material. Feldman wrote everything by hand and because he was so shortsighted the classic image is of this hulking figure hunched over his scores writing the most detailed music with beautiful penmanship. He talked about the pace at which he wrote being very important, “don’t push the notes around” as a mantra, and I think that the handwritten aspect played a significant role in the deliberate pace of his music. It’s another way we get closer to Feldman, reading a printed edition of his music just isn’t the same.

John Cage lived for a time in a building at 326 Monroe Street (since demolished) almost underneath the Williamsburg Bridge. Morton Feldman joined him for a year. Christian Wolff, David Tudor, and Merce Cunningham were always there. There isn’t a comparable place in recent music history. You could take Vienna with Haydn and Mozart, Schubert and Beethoven and Louis Spohr, running around in the same streets but imagine if they were closer together in age and hung out at Haydn’s place all the time! There’s nothing like it. I’ve spent a lot of time with Feldman’s scores and writings, wanting to get closer and closer to him. I’m lucky enough to play in a string quartet with three other guys who share my obsession (and we’ve got some serious Feldman-heads in The Knights too) and we’re always tickled by new things we find in his music. The little winks at the performer, the tiny, almost imperceptible changes that happen when he repeats material. Feldman wrote everything by hand and because he was so shortsighted the classic image is of this hulking figure hunched over his scores writing the most detailed music with beautiful penmanship. He talked about the pace at which he wrote being very important, “don’t push the notes around” as a mantra, and I think that the handwritten aspect played a significant role in the deliberate pace of his music. It’s another way we get closer to Feldman, reading a printed edition of his music just isn’t the same.

As musicians of the 21st century we are all of course familiar with John Cage. There is before Cage and there is after Cage. Cage gathered a circle of composers around him. Morty was his intellectual equal. Christian Wolff was the boy genius of the group. David Tudor the consummate performer/composer. (These are obviously superficial descriptions that one could use to pitch a network TV situational comedy, but I’m writing this between rehearsals of an Arensky Piano Quintet and a Rachmaninoff string quartet so give me a break.) Cage and his partner Merce Cunningham invited the composer Earle Brown and his dancer wife Carolyn to join the group, which Feldman apparently objected to and the group of composers broke up. I would love to have been there to drink and debate late into the night with these guys at the Cedar Tavern on University Place. Feldman, Tudor, Cage and Brown are all gone. I’ve met Brown’s widow who is lovely. I’ve worked with Christian Wolff (now 80) who is incredibly kind. People who knew them and knew them well are still walking around these streets. I know some of these people. The thing is. ..I’m embarrassed to ask about them but especially Morty in particular. I feel like I’ve gotten to know him so well through his music and his writings that he has turned into the superhero who I know. Like I’m Jimmy Olsen with a viola instead of a camera. I know he was a flawed human. I am aware of the feeling that the longer I wait to talk to people about him, that “too-late” is going to rush up against me. I guess there is the humility factor, like “they must be so sick of talking about him”. Magnificent composers in their own right, I feel that if I’m playing their music, they deserve my total focus, not some fanboy begging “Tell me about Morty.” What do you think? Should I get over my shame?

..I’m embarrassed to ask about them but especially Morty in particular. I feel like I’ve gotten to know him so well through his music and his writings that he has turned into the superhero who I know. Like I’m Jimmy Olsen with a viola instead of a camera. I know he was a flawed human. I am aware of the feeling that the longer I wait to talk to people about him, that “too-late” is going to rush up against me. I guess there is the humility factor, like “they must be so sick of talking about him”. Magnificent composers in their own right, I feel that if I’m playing their music, they deserve my total focus, not some fanboy begging “Tell me about Morty.” What do you think? Should I get over my shame?

After playing so much of his music, reading so much of his writings, and listening to interviews and pouring over pictures, I feel like I have a lifetime of trying to understand Morton Feldman ahead of me and that if an organic conversation develops with a musician who remembers him, it is meant to happen. On top of that I feel like I continue to deepen my understanding though the artists he was connected to, people he was close with and drew inspiration from more than most composers: Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, Philip Guston, and Mark Rothko.

I feel like Mark Rothko is a gateway drug to modern art. When I first saw a Rothko, probably in high school, I knew I didn’t “get it” but I knew that I loved it. Maybe I loved the idea that it wasn’t necessary to “get” anything. What struck me at the time was the simplicity and the bravery of the paintings. Just shapes and color. Now I know that Rothko was working, obsessing, winding, layering, beating his head against the brick wall to get to that simplicity. Now I know that what’s behind that simplicity is incredibly complicated. It’s the way I look at Feldman too. I’m thrilled to be performing Feldman’s Rothko Chapel at the Ojai Festival. I’ve visited Rothko Chapel in Houston only once and I keep meaning to go back, but the emotional and spiritual experience of that first visit looms massively in my mind. I am not a religious person. Their website calls it “an intimate sanctuary available to people of every belief” and that kind of attitude will get me in the building. I experienced that calm, peaceful feeling that you often get in church or synagogue but after a time of sitting there with the 14 canvases of Rothko, I started to feel an electrical current passing through me which built and built until my heart was racing and then gradually subsided. This is what I hope we will get to experience together during our performance of Feldman’s music inspired by this place and his long relationship with Mark Rothko.

I feel like Mark Rothko is a gateway drug to modern art. When I first saw a Rothko, probably in high school, I knew I didn’t “get it” but I knew that I loved it. Maybe I loved the idea that it wasn’t necessary to “get” anything. What struck me at the time was the simplicity and the bravery of the paintings. Just shapes and color. Now I know that Rothko was working, obsessing, winding, layering, beating his head against the brick wall to get to that simplicity. Now I know that what’s behind that simplicity is incredibly complicated. It’s the way I look at Feldman too. I’m thrilled to be performing Feldman’s Rothko Chapel at the Ojai Festival. I’ve visited Rothko Chapel in Houston only once and I keep meaning to go back, but the emotional and spiritual experience of that first visit looms massively in my mind. I am not a religious person. Their website calls it “an intimate sanctuary available to people of every belief” and that kind of attitude will get me in the building. I experienced that calm, peaceful feeling that you often get in church or synagogue but after a time of sitting there with the 14 canvases of Rothko, I started to feel an electrical current passing through me which built and built until my heart was racing and then gradually subsided. This is what I hope we will get to experience together during our performance of Feldman’s music inspired by this place and his long relationship with Mark Rothko.

When I’m faced with a mystery like “Who was Morton Feldman?” or “Why does Rothko make me feel that way?”, I keep coming back to something Feldman often talked about and phrased in different ways. In an essay called “Predeterminate/Indeterminate,” he put it as, “Philip Guston once told me that when he sees how a painting is made he becomes bored with it.”

Feldman never wanted to have a system of composition, and if he could hear the system in a piece of music it would drive him crazy. So as I search to understand how these masters of their art make me feel something so powerful, I know in the back of my mind that I hope I never get to the bottom of it. In fact I’m convinced that with their greatest works I never will and that’s a very comforting thought.