Music to Painting: My Encounters with Pierre Boulez

[nggallery id=8]Click images above to view full size; listen to Le Marteau sans Maître on Spotify below

Los Angeles-based artist and psychoanalyst Desy Safán-Gerard met Pierre Boulez when young, and continued to cross his path as her career developed. She created a series of paintings of his work “Le Marteau sans Maître”. She was kind enough to write us a piece documenting her history with Boulez and the development of the paintings (shown above).

I was only 19 years old when I first met Pierre Boulez. I was singing in the choir of the University of Chile, the country where I was born. He was a fledgling conductor who was the music director in the famous theatrical company of Jean-Louis Barrault and Madeleine Renaud (the same Barrault of fame who, several years earlier, had played the role of the mime in the French classic film Les enfants du Paradis).

During his visit to Chile, Pierre Boulez needed a choir for the music in a play being performed by Barrault and Renaud, Cristobal Colon, written by Paul Claudel with music composed by Darius Milhaud. I was lucky to be selected as one of the sixteen musicians from our choir to perform during the play, under the baton of Pierre Boulez.

We were singing in the pit of the Teatro Municipal de Santiago, and it was a revealing experience for a young girl like me. I was impressed by Boulez directing us and recognized instantly his immense talent and creative streak.

I had the good fortune to meet him many years later, after I had moved and settled in Los Angeles. I told him I had sung for him in Chile, to which he replied that the time he had spent there had been the happiest in his life. I added that it was also one of the happiest times in my own life, particularly when at night, after the rehearsals, a large group of actors, musicians and choristers would go to get coffee together. I would return home very late, finding my parents upset at my bohemian life style.

Sometime in 1984, Boulez was in Los Angeles and I attended a lecture on creativity that he gave. I asked him permission to “paint” his nine movements of Le marteau sans maître. With his French logic, he responded that, since René Char had given him permission to write music to his poem and to even use the poem title for his composition, he was now delighted to give me a similar permission to translate his music into my paintings.

My attempt to do a visual translation of Boulez’s Le marteau sans maître had to do with my wish to really comprehend this piece of music. I was fascinated with the complexity and beauty of the movements. In order to do paintings based on Le marteau, I would have to listen to them many times and get to understand each movement from the inside out. It was as if I wanted to get into Boulez’s mind and relive his creative process along with him. This particular intimacy called for small format work, so I used watercolor, micropens, and pencils on paper measuring eighteen by fourteen inches. In addition, and perhaps more importantly, these paintings represented my wish to forget my own subjective moods to pursue an objective depiction of Boulez’s sounds.

I began by taking walks in the Palisades Park in Santa Monica while listening to the nine movements, spending a lot of time with each one. I would then go back to my studio and listen to them again, taking notes with colored pencils. The overall colors of these paintings were the result of my subjective experience of each movement. For example, in three of the paintings I used a golden yellow for the background, in four I used a soft green for the background and in the last two I used a soft magenta. In all of them, the color was uneven, leaving enough visual elements to encourage me to play and invent new shapes. These areas without color or small areas of different and subtle pastel colors were meant to represent the irregularities of the sound events and help in the overall design of the movement. In all nine I painted a one-inch border using the same color in a deeper shade in order to create a subtle inside frame. The reason for this is that I already knew I wanted to portray the freedom of Boulez’s music by having the events within the frame extending outward and going over that inside frame. This was to be the most important feature of each painting.

As far as what went into the framed areas, I tried to find the visual equivalent of each sound. It was clear to me that the flute would be represented by a thin silver line moving irregularly up and down on the paper (following the music). A bassoon was represented by a thick line with a burgundy color that moved rather slowly. A thicker gold line represented the movements of the viola and cello. In paintings eight and nine, a thicker burgundy line represented the female alto voice featured in those movements.

Boulez tends to use many percussion instruments and Le marteau is no exception. I attempted to represent the reverberation of the percussion instruments with concentric circles drawn with pencil from a point in the center of the sound. The complexity of sounds was represented by having different lines crossing and coming together in various areas of the paper. The accidental happenings on the paper helped guide the intersecting lines. In spite of my desire to be loyal to Boulez, I felt tremendous freedom to invent the visual elements as needed.

Several years later, Pierre Boulez (by then a well-known conductor and composer) was in Los Angeles conducting Bruckner’s ninth. I visited him during rehearsal, hoping he could come to my studio to see the finished paintings. He could not find the time for it, but requested that I bring them to him after one of his rehearsals. I did, lugging two large suitcases. I lined up the nine paintings against the wall and to my surprise and delight, he pointed to one of them saying, “That’s my number four”, and to another, “That’s my number six” and so on until he identified each of my paintings with the exact movement of the music I had reproduced. I was blown over that he could respond so accurately to the structure of my paintings. All my efforts to translate his music had been worth it because Boulez had accepted and validated my work!

I treasure these paintings so much that I have been reluctant to sell any of the series. They are a memento of one of my most precious musical and visual experiences, and I would only let them go if Pierre Boulez would want them for IRCAM (L’Institut de recherche et coordination acoustique/musique), which he founded.

I have continued to be inspired by Boulez’s music. In 2012, I did a performance at the Galerie Dufay/Bonnet in Paris where I painted with both hands while a nude model moved to Boulez’s Notations. I was sad that he could not come to this performance because he was in Chicago having eye surgery.

Desy Safán-Gerard

April 2015

Venice, California

Pierre Boulez on his 90th Birthday – A Personal Memoir

Pierre Boulez on his 90th Birthday – A Personal Memoir

Richard S. Ginell

CLASSICAL VOICE NORTH AMERICA – March 27, 2015

Read article on the Classical Voice website >>

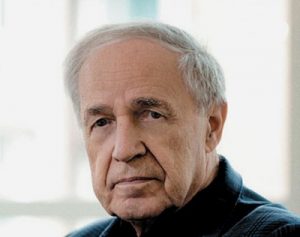

On Pierre Boulez’s 90th birthday, I’d like to share a few memories of watching this once-controversial, now-revered paragon of 20th century music over the decades.

– Hearing Boulez’s shattering, clear-as-glass rendition of Debussy’s La Mer in 1984 for the first time, played live by the Los Angeles Philharmonic in UCLA’s Royce Hall, which had just re-opened to the public after a thorough renovation. The word “revelation” is overused and undervalued, but this was a REVELATION, exploding all pre-conceptions I had before about the piece and coloring whatever I’ve thought about it since.

– His press conference just before the above concert. Here was the new, genial, conciliatory Boulez, even expressing surprising (for us at the time) admiration for Frank Zappa, whose music he had just recorded. But then, when asked about minimalism, the old, confrontational Boulez suddenly leaped out. He heatedly equated it with neo-classicism, calling the latter “A cancer!”

– A moment six minutes into the first West Coast performance of Boulez’s electro-acoustic masterwork Répons in a gymnasium on the UCLA campus, Feb. 1986. At that point, Boulez flicked his fingers and dramatically triggered a gorgeous, tingling, shimmering wave of surround-sound electronics that filled the room. It occurred to me right then that all of the conventional thinking about Boulez was wrong, that he was really a colorist first and foremost, not a systems man. I went back for seconds the next evening.

– The 1996 Ojai Festival. It was one of the most sweltering festivals ever, 97 degrees all weekend. Even the formal Boulez shed his usual business suit and tie for shirtsleeves by the last day. But he carried on – among other things, leading his new … explosante fixe … like a magician and a transformed Mahler Fifth that indicated a new depth in his understanding of a composer to whom he came late. And as Boulez returned to the wings after the final bar of the final concert, exhausted from the heat, I could hear him mutter, “The end.” But it wasn’t.

– Back to Ojai, 2003. I managed to sneak into an ongoing Boulez rehearsal of Mahler’s Ninth, as I had in his previous visit for Mahler 5. I quietly took a seat on one of those rustic benches that no longer exist, opened my score to the middle of the first movement – and within five minutes I was in tears. This supremely rational, left-brain man had managed to find the emotional core of Mahler without grandstanding, without deviating from the page. Arnold Schoenberg said it – “Heart and brain in music.”

Happy birthday, Pierre!

As Pierre Boulez turns 90, conductor-composer’s impact beyond question

As Pierre Boulez turns 90, conductor-composer’s impact beyond question

Mark Swed

LOS ANGELES TIMES – March 25, 2015

Read article on the LA Times website >>

Pierre Boulez — who has done as much as if not more than any other living composer and conductor to change the way we think about and make music — turns 90 on Thursday.

For seven decades, he has developed elaborate new approaches to the use of sound and materials. He has invented a style of conducting that brings details to life. And he has stimulated the creation of new institutions, most notably the computer music research institution in Paris known as IRCAM and the new music group Ensemble Intercontemporain.

For Europe, Boulez’s 90th is a monumental milestone. There have been in the past week massive birthday tributes at London’s Barbican Centre and the new Philharmonie in Paris (which Boulez had long lobbied for). Five box sets of CDs and DVDs have come out, or are about to, that contain the vast majority of Boulez’s recordings as composer and conductor. Poke around the BBC Radio 3 and Radio France websites for exceptional troves of Bouleziana.

Boulez’s influence has been pervasive in the U.S. as well. As music director of the New York Philharmonic in the 1970s, he tried to reinvent the orchestra as a late 20th century institution. Having won 26 Grammys over the years, he was given the lifetime achievement award at this year’s ceremony in February.

But Boulez fever has not captured the imagination of U.S. orchestras this week. The Chicago Symphony and Cleveland Orchestra, two ensembles to which Boulez has had close ties, had their Boulez moment months ago.

What about the other two orchestras with Boulez connections? Bizarrely, rather than pay tribute to the birthday boy Thursday night, the New York Philharmonic premieres a new John Adams violin concerto. The L.A. Philharmonic, on an Asian tour, performs Adams’ “City Noir” in Seoul. Adams has long bristled against the hegemony of the European Modernism of which Boulez became a symbol.

The fact is: No one can escape Boulez, whether it is as a follower or rebel. The New York Philharmonic may want nothing to do with the big birthday of a former music director, but two possible candidates to become the orchestra’s next are Esa-Pekka Salonen and David Robertson, both of whom learned directly from Boulez that precision and passion are not antithetical.

The Los Angeles Boulez neglect in general is particularly troublesome. Boulez made his U.S. conducting debut in 1956 at the Monday Evening Concerts, where he led the U.S. premiere of his most famous work, “Le Marteau sans Maître.” It was a great event. Stravinsky was on hand for it.

Nine years later and almost exactly 50 years ago, on March 26, 1965, Boulez celebrated his 40th birthday conducting the world premiere of his “Éclat,” which was commissioned by the Monday Evening Concerts for the opening of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It was another grand event. Stravinsky was there as well and went to dinner with Boulez afterward. This anniversary is going unacknowledged in LACMA’s 50th-anniversary activities.

After he left New York, Boulez became a regular conducting the L.A. Phil, but he was already by then a fixture at the Ojai Festival, which will pay considerable tribute in June with several Boulez chamber pieces programmed.

But we have other choices for the big day. Last year Deutsche Grammophon released a collection of Boulez’s complete works in performances by the composer or musicians he has coached. The 11-CD set is an immersion in admittedly intellectually intense pieces but ones that contain a gorgeous sensuality and an exciting appropriation of the glittery sound world of Asian and African musics.

Boulez’s style is explosive. He detonates a germ of an idea and, like a seed, it grows a sonic forest. The common fallacy is that pieces as highly and intricately structured as these require technical understanding. But you don’t need to be a botanist to be stirred by a field of wild flowers.

Sony has collected Boulez’s vibrant recordings made in the ’60s and ’70s with the Cleveland Orchestra, New York Philharmonic and the BBC Symphony, covering music from the Baroque to first performances of his own work. DG, meanwhile, has just brought out all of Boulez’s glorious performances from Chicago, Cleveland, Berlin and elsewhere of 20th century scores.

Next month, a collection of Boulez recordings from the 1950s with his Parisian new music ensemble Domaine Musical will chronicle his early avant-garde approach. This is where Boulez invented a style of conducting, often compared to that of a French gendarme directing traffic. For those wishing to see the master in action, EuroArts has collected 10 Boulez DVDs under the title “Emotion and Analysis” that include live Boulez performances, documentaries and Boulez’s illuminating analyses of his own music.

Boulez is said to be frail. Failing eyesight and a series of falls have kept him off the podium the past three years. But despite the lapses in the U.S., his legacy has never been more assured.

Concert Review: CSO Presents a Salute to Pierre Boulez

Concert Review: CSO Presents a Salute to Pierre Boulez

John von Rhein

CHICAGO TRIBUNE – November 15, 2014

Read article on the Tribune website >>

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Beyond the Score series has been remiss in not exploring the music of living composers. Creative director Gerard McBurney made amends with his most recent presentation, “A Pierre Dream: A Portrait of Pierre Boulez,” a program honoring the eminent composer and conductor in advance of his 90th birthday next March.

The first of two weekend performances, given Friday night at Symphony Center, was not so much a concert of the French master’s works as an illuminating theatrical phantasmagoria about how Boulez’s intricate music is made – and even more about the aesthetic issues that have preoccupied him from his earliest compositions of the 1950s, when he and fellow young firebrands rattled postwar Paris with their avant-garde screeds, to the slow trickle of works the elder statesman of musical modernism has painstakingly produced up through the present.

A second performance was due on Sunday afternoon, and both performances included postconcert Q&As with the creative team.

McBurney’s feat – in his highly inventive, 90-minute collage of musical excerpts, live and recorded speech, documentary footage, light and video projections, all encased in an original scenic design by the famed architect Frank Gehry – was to make Boulez, who is nothing if not the most non-theatrical of composers, an apt subject for the kind of heightened, poetic music theater that’s emblematic of Beyond the Score.

“A Pierre Dream” (the title was Gehry’s) is structured around interview material with Boulez, the CSO’s conductor emeritus, much of it filmed last year at his home in Baden-Baden, Germany. Though his eyesight is reportedly greatly impaired and he looks rather frail, his mind was as sharp as ever as he reflected on why just about everything he has composed he considers a work in progress, music subject to endless revision.

“For me each composition is like a labyrinth, and a labyrinth can go on forever,” he observed, echoing sentiments Leonardo da Vinci expressed centuries before: “A work of art is never finished, only abandoned.”

Whereupon an ensemble of 18 CSO musicians and guests under conductor Pablo Heras-Casado (Cliff Colnot did the musical preparation, though he was uncredited in the printed program) furnished examples of Boulezian elaboration – the expansion of his 1977 “Messagesquisse,” for example, into both the 1984 “Derive 1” and the greatly expanded “Derive 2” of 2006, which Boulez apparently has never stopped tinkering with.

A chain of echoes and connections thus emerged as to suggest an overarching continuity – a kind of meta-music, if you will – between pieces of different periods. Hearing selections from 16 Boulez works one after the other was like walking through a garden of sculptures, each slightly different from the other but all in the same style. Boulez early on identified those musical elements and relationships he wished to penetrate through his art, and he has spent the rest of his composing life exploring and refining them. Thus you heard the music of a young man in his 20s alongside that of a seasoned artist in his 80s – all of it indelibly Boulez’s.

Audience members who may have feared this all would be impossibly cerebral, forbidding, impenetrable stuff were in for a pleasant surprise: Much of the music, including two of Boulez’s improvisations on Mallarme texts (from “Pli selon pli”) and movements from his classic “Le marteau sans maître”, revealed a shimmering, crystalline subtlety as exquisitely wrought as anything by Debussy, a composer to whom Boulez professes a profound debt. Much of Boulez’s music is far more accessible than most classical listeners think.

Gehry’s stage setup, artfully enhanced by Mike Tutaj’s projection design and Jason Brown’s lighting, was ingenious. It consisted of a dozen rectangular panels that were arranged in various configurations by a team of seven black-clad actors. It was onto these screens that the visual elements were projected – including shots of the musicians performing in the moment, Boulez in conversation with Igor Stravinsky and other rare archival footage. The simultaneity of aural and visual information very much mirrored what goes on in Boulez’s music at any given moment.

There were occasional lapses, as when the projections devolved into little but blurred, watery abstract shapes, and I would have preferred hearing more pieces played in their entirety, rather than chopped up to be sandwiched around the spoken portions. Perhaps McBurney will pull a Boulez and do a bit of tinkering himself before the live version of “A Pierre Dream” travels to Ojai, Berkeley and elsewhere beginning next year.

In addition to Heras-Casado’s precise direction, one cannot praise the performers too highly. Among them were soprano Mellissa Hughes, pianists Winston Choi and Amy Briggs, concertmaster Robert Chen, flutist Jennifer Gunn and clarinetist John Bruce Yeh.

“I want to have the surprise and enjoyment of discovery,” Boulez said during one of the filmed interviews, speaking of his objectives as a composer. But he could just as well have been speaking of what most of the audience took away from “A Pierre Dream.”