What’s on your Bookshelf Recommendations

In our current time of endless Zoom meetings or even when watching the news, we have taken notice and peeked curiously at other people’s backdrops. Inevitably, a bookshelf seems to be a frequent ‘prop’ — always lined with what looks like interesting books…and so we all wonder, what’s on their bookshelf? What is there that might interest me, inspire or entertain me during these times? What might I learn about the person on screen that I didn’t know? For this, we turned to our Festival family – Barbara Hannigan, George Lewis, Thomas W. Morris, and Miranda Cuckson – to share with us their own inspirations. What we come out with to share with you is a multitude of fascinating reading and music resources. Enjoy!

BARBARA HANNIGAN

Books:

Nuria Schoenberg-Nono – Arnold Schoenberg: Playing Cards

Arnold Schoenberg – Theory of Harmony

Carl Schorske – Fin-de-Siecle Vienna: Politics and Culture

Music:

Alban Berg – Lulu

George Gershwin – Girl Crazy Suite

GEORGE LEWIS

Books:

Naomi André – Black Opera: History, Power, Engagement

W.E.B. Du Bois – The Comet

Luc Boltanski & Eve Chiapello – The New Spirit of Capitalism

Uwe Johnson – Anniversaries: From a Year in the Life of Gesine Cresspahl

Kim Stanley Robinson – The Ministry for the Future

Music:

Wagner – Lohengrin

Wagner – Parsifal

Composers he is following: Andile Khumalo, Hannah Kendall, Courtney Bryan, Leila Adu-Gilmore, Jessie Cox, Jason Yarde, Daniel Kidane, Tania León, Alvin Singleton

Thomas W. MORRIS

Books, etc:

Joshua Wolf Shenk – Powers of Two: How Relationships Drive Creativity

Heidi Waleson – Mad Scenes and Exit Arias: The Death of the New York City Opera and the Future of Opera in America

Stave Jigsaw Puzzles, Vermont

Music:

J.S. Bach – Cantatas

Fritz Reiner – Chicago Symphony Play Works by Ravel and Debussy. RCA Red Seal, 1986, CD

Fritz Reiner & Chicago Symphony Orchestra – The Complete RCA Album Collection, CD

MIRANDA CUCKSON

Books:

Dominique Fourcade – Henri Matisse Ecrits et propos sur l’art

Charles Mackay – Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

Joseph Szigeti – Szigeti on the Violin

Tobias Wolff – This Boys Life: A Memoir

Music:

Alban Berg – Lulu

Blue Heron (Renaissance Choir)

Christelle Bofale (Singer/songwriter)

Jon Hassell (Experimental trumpeter/composer)

Paco de Lucia (Flamenco guitarist)

Johannes Ockeghem (Renaissance composer)

ARA GUZELIMIAN

Books:

André Aciman – Out of Egypt: A Memoir

Eric Ambler – A Coffin for Dimitrios

Ishmael Beah – Radiance of Tomorrow

Tove Jansson – Travelling Light

Penelope Lively – Moon Tiger

Tayeb Salih – Season of Migration to the North

Zadie Smith – Swing Time

Lizabeth Strout – My Name is Lucy Barton

Miral Tahawi – Brooklyn Heights: An Egyptian Novel

Music

John Adams – The Wound Dresser

Smithsonian Anthology of Blues

Blind Willie Johnson – Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground

Vikingur Ólafsson playing Bach – Concerto in D minor, BWV 974 – 2. Adagio

Read Ara’s “Music for our Time” blog

Music For Our Time

A Message from Ara Guzelimian, Artistic & Executive Director

I write this on a bright November day, the air fresh with the crispness of the season. It has been a time of extraordinary events, marked a few days ago by an election of extreme division. We continue to be in the midst of an unprecedented pandemic, which has brought much loss, separation, and isolation. All of that is compounded by the racial and economic fissures made apparent by events of the past year.

How do we measure this time in our innermost thoughts? Many years ago, I first met Peter Sellars at a conference in San Diego where he was giving a talk. His remarks have stuck with me, growing in importance with the passage of time. Peter said that our response to the arts is one of the few truly private experiences we have at a time of very little privacy. We encounter a book, a play, a piece of music, a work of art, a dance; we may express a public opinion and may even try to second-guess what a “correct” and “sophisticated” opinion might be. But when all is said and done, when the lights are out and our head hits the pillow, we are left alone with our experience of the art. We love it or we don’t, it speaks to us or it doesn’t, we understand it or we are left confused. But, in the end, we feel what we feel and think what we think.

Like so many of us, I have turned to music of every variety imaginable to keep me company in this roller-coaster time. I’ve found myself returning to a Smithsonian anthology of the blues that I’ve had for years but had overlooked more recently. There is such richness in this tradition and, as B.B. King observed, “blues is a tonic for what ails you. I could play the blues and not be blue anymore.” One of the most moving discoveries among these old recordings is this one, sung and played by Blind Willie Johnson (inset photo), that summons up a well of human expression without a single word being uttered. Here is a recording made nearly 100 years ago that reaches out across time and speaks to us with amazing currency. This is the raw power of music in its ability to express deep emotion.

My other constant has been the music of Bach, especially in the hands of great pianists. Bach’s music is informed by his unshakable faith, an abiding humanity, as well as a sense of order and design. In working with John Adams to plan the 2021 Ojai Festival, I have been listening intently to the recent recordings by one of our artists, the Icelandic pianist Víkingur Ólafsson, a pianist as at home in Bach as he is in the music of Philip Glass. His recent Bach recording is one of exceptional beauty, and I have returned to it often to provide a grounding in this disrupted time. As Víkingur wrote, “everything is there in Johann Sebastian’s music: architectural perfection and profound emotion.” Here is the Adagio from Bach’s Concerto in D Minor, BWV 974:

I happily anticipate Víkingur’s participation next year and am so grateful to John Adams for suggesting him as one of the first guest artists to invite. John himself has had an uncanny ability to give voice to American experience throughout his career – he is a musical chronicler of our times. In recent days, I found myself thinking about The Wound Dresser, a 1989 setting of Walt Whitman’s poem of the same name. In it, Whitman documents his experiences tending to the Civil War wounded in makeshift field hospitals.

In listening recently to The Wound Dresser, I have been so struck by the resonances with our own moment in time – the deep divisions in the country on one hand and the boundless generosity of so many health workers and caregivers in this pandemic on the other. Whitman writes “Thus in silence in dreams’ projections, / Returning, resuming, I thread my way through the hospitals, / The hurt and the wounded I pacify with soothing hand.”

John wrote about the work, “It is a statement about human compassion that is acted out on a daily basis, quietly and unobtrusively and unselfishly and unfailingly.” Another [Whitman] poem in the same volume states its theme in other words: ‘Those who love each other shall become invincible . . . ‘”

And so, we are reminded that artists are our truth-tellers and our chroniclers, their work our necessary companions through thick and thin. I am also reminded that we turn to the arts particularly in trying times. As we approach the 75th Festival in June, it is meaningful to recall that the Festival was founded in 1947, when the world was just barely emerging from World War II. The Festival’s very existence comes from an act of hope and optimism at a time of rebuilding in the face of adversity. In that spirit, we hold the promise of the next Ojai Festival as a similar act of faith.

When we gather together to listen to music, we assert our humanity, our belief in the arts, and in community. Thanks to each of you for creating the warm and welcoming spirit of community that defines the Festival. I am so gratified to be working with the musicians who will bring to life the 75th Festival. And I relish the promise of listening to their music in your company.

Joan Kemper Way

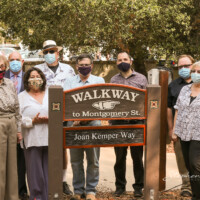

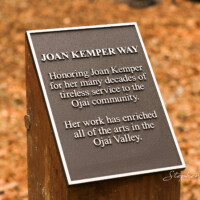

On a characteristically hot and sunny Ojai September day, a small group of people gathered in Libbey Park to honor Joan Kemper, a true community hero. The path connecting the Ojai Art Center with Libbey Park was officially renamed Joan Kemper Way, honoring a woman who has been central to so many community organizations and so many worthy endeavors throughout Ojai. She is one of those treasures who makes the quality of life better not only for those around her but also for so many people she may never meet.

Joan was a relatively recent arrival to Ojai when she stepped in to serve as Executive Director of the Ojai Festival in the early 1990s. I had the huge pleasure of working with her for several years and marveled at her boundless gifts for making things happen. She is one of those remarkable people who has never met a problem she couldn’t solve. The Festival was floundering without leadership at the time she took it over – there was no task to large or small for Joan, who is one of the most persuasive and creative problem solvers I’ve ever met.

In one of my fondest memories, Peter Sellars was directing a fresh re-thinking of Stravinsky’s Histoire du Soldat with Music Director Pierre Boulez conducting in 1992. Peter wanted to capture Stravinsky’s original intent of a certain street-theater atmosphere, updated to the present time. And so he wanted to have a full-size pickup truck on stage at Libbey Bowl to capture that spirit. How to find a loaner pickup truck and get it up on stage? Leave it to Joan to draw upon friends across the community to help with getting the truck, creating a series of safe ramps, and getting it up on stage.

Good things happened whenever Joan is around, particularly throughout the Ojai community. She has a way of rallying people to a common cause, with music and theater being especially close to her heart. She gets you to pitch in and then she makes the whole thing such great fun that you end up thanking her. These days, Joan may slyly say, “you know, I’m basically a hundred years old” – it’s only a slight exaggeration – but her wonderful indefatigable spirit seems to me as lively and inspiring as it was on the day I met her.

I am grateful, like so many others, to travel on Joan Kemper Way! Long may you brighten our lives, Joan.

- Ara Guzelimian, Artistic & Executive Director

Ojai photos by Stephen Adams, Peter Sellers and Pierre Boulez by Betty Freeman

Play Music on the Porch – A Virtual Global Effort

Now more than ever, creative expression is important to join together even in the virtual world!

The Ojai Festival’s BRAVO education & community program is delighted to partner with Porch Gallery Ojai by organizing performances of Ojai-area musicians and students for #PlayMusicOnThePorchDay on Saturday, August 29, beginning at 10am.

For the fifth time, Porch Gallery Ojai will join in this global effort to continuing the tradition of singing and playing to re-establish music as an inclusive, shared and participatory celebration of life. Set your calendar for August 29 when we will launch music videos, played in porches across the Ojai Valley! Videos can be accessed, here, on our website or on our Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/ojaifestival/.

“The BRAVO program is pleased to work with the Porch Gallery Ojai in this year’s Music on the Porch project. Local musicians enrich the BRAVO program throughout the year, and we feel deeply grateful for their contributions once again, to help us all connect through music. The arts can help us build bridges of hope,” shared BRAVO coordinator Laura Walter.

What is Play Music On The Porch Day?

In 2013 the founder, Brian Mallman, of Play Music on the Porch Day decided to share the idea – “What if for one day everything stopped…and we all just listened to the music?” – with the world. Since then, thousands of musicians from at least 75 countries and over 1450 cities have participated and this movement continues to grow every day with artists, regardless of their differences, are finding common ground through music. Learn more here >

Ojai’s line-up of wonderful musicians providing music for all to enjoy, and inspire us to revive the tradition of gathering, singing and playing music outside with friends and family virtually and safely social distancing!

Chaparral Swing Band

Celtic Nut (Eilam, Noahm and Edaan Byle)

Licity Collins

Fran Gealer

Coree Kotula

Ruby Skye

Kaylie Turner

Babette & Bob Vasquez

Jess Wayne

Beginning and Homecoming: Message from Ara Guzelimian

A beginning and a homecoming. It is rare for the two to coincide. A few days ago I experienced a moment of transformation – I stepped down as Provost and Dean of the Juilliard School after 13 ½ rewarding years and became Artistic and Executive Director of the Ojai Festival (I seem to have a thing for compound titles!). Of course, I am hardly new to Ojai, having been associated with the Festival in one capacity or another for several decades now. But this feels like a real homecoming, a return to what I love so dearly.

And what a time! We are in the strangest of circumstances, trying to understand practically and philosophically what is meant by “social distancing” when we humans are such fundamentally social creatures. In the midst of all this, the deep underlying fissures of American society burst unstoppably with the horrifying death of George Floyd, another moment in centuries of such horrifying incidents laying bare the disease of racism.

We shared in the most meaningful way that we can, which is letting powerful art speak the truth. The Festival brought renewed focus to the world premiere of the first version of Josephine Baker: A Portrait from the 2016 Festival, written by Tyshawn Sorey with words by Claudia Rankine, sung by Julia Bullock and directed by Peter Sellars.

Sadly, the 2020 Festival created by Matthias Pintscher and Chad Smith was cancelled in the face of the coronavirus pandemic, taking away the gathering at Libbey Bowl that we all cherish so much. In its place, there was a virtual festival with the joy of keeping company with Matthias Pintscher, Olga Neuwirth, the Calder Quartet, and Steve Reich, all so generously participating to honor the spirit of the planned 74th Festival. It was so incredibly heartening to gather together in multiple Zoom screens of virtual Patron Lounges ahead of each evening’s Festival stream and to have the pleasure of each other’s company in our mutual affection for Ojai and the Festival. Thanks to each of you for participating, watching, sending us some lovely notes, and generously giving financial support to help sustain the Festival in this trying time. We are what we are because of you, especially in these challenging days.

Many of you commented on your pleasure in the virtual time spent with Matthias and Olga. I’m delighted that our colleagues at the Pierre Boulez Hall in Berlin have created their own virtual new music festival, anchored by works of Pierre Boulez, with newly written pieces by both Olga and Matthias, so I am happy to direct you to what sounds like an Ojai in Berlin. Click here to view.

We have all had our ups and downs during this time of isolation, which makes us doubly grateful for those moments that brighten our spirits. I had just such an experience in a phone call with John Adams, the Music Director of the 2021 Ojai Festival, as we began our planning for what is to be the 75th edition. John and I spoke for an hour just dreaming up ideas about favorite music and musicians, discoveries we couldn’t wait to share with each other, and suddenly the whole perspective shifted – instead of talking about what we were missing in our isolation, we were talking with love and excitement about what will animate Libbey Bowl in a year’s time. It was like breathing oxygen again!

Although a milestone anniversary year might suggest a retrospective, John was having none of that. He wants an absolutely forward-facing festival that celebrates the next generation of composers and musicians. Future Forward was born at that moment as the underlying driver of the 2020 Festival. We have invited a number of brilliant young composers and performers to form the core of the coming festival. We also decided to form an all-star, hand-picked ensemble of musicians to form the featured “band” of the Festival, focusing on the incredible talent to be found in California and around the U.S. We will make the first announcement of next year’s Festival near the end of July, and you will be the first to know. Stay tuned!

In closing, I can’t help but relay a wonderful experience I have had in the past week. I was to be in Bamberg, Germany to serve on the jury of the Mahler Conducting Competition. Alas, it was not to be as the European Union continued a strict ban on U.S. travelers because of the high incidence of the virus in this country. Happily, I was able to take part virtually, awakening each morning at 3 a.m. to watch the livestreams of the sessions and then participating via Zoom in the jury room deliberations. I was thrilled to work again with the wondrous Barbara Hannigan, a fellow juror doubling as soprano soloist in the closing performance of the Mahler Fourth Symphony. Barbara is an extraordinary artist and human being, as we all well know from our time with her at the 2019 Festival. Her generosity and insight informed the conversations; her luminous singing in the Mahler gave it its closing benediction. You can watch the performance here with the fourth movement beginning at 1:16.50.

And in the course of a deeply meaningful week of music and conversations, everything came full circle. The guiding spirit of the competition is Marina Mahler, the composer’s granddaughter, who is an irresistibly vibrant personality. In one of our conversations, I suddenly remembered that she had a long chapter in her childhood in Los Angeles. Her mother, the sculptor Anna Mahler, moved with Marina to Los Angeles to live with Alma Mahler, Gustav’s widow who was then based in Beverly Hills. It was in talking about our Southern California roots that Marina told me that she went to the Ojai Valley School, beginning at the age of seven! Who would have thought that there would be one degree of separation between Gustav Mahler and Ojai . . . .

I took that as sign to redouble all our efforts in nourishing and supporting this unlikely treasure in a wooden bowl in a town park in the most heavenly setting. I have always thought of the Ojai Festival as something of a miracle. With your help, I will do all within my abilities to sustain and renew this beloved festival.

Next year in Libbey Park!

With thanks and warm regards,

Ara Guzelimian

Artistic and Executive Director

P.S. Claire Chase and I have kept up a lively exchange of messages during these past four months as we record and send various experiences of bird song to cheer each other up. Claire has a decided advantage as a flutist! In honor of that exchange, I send you Claire and bird song, as channeled by Dai Fujikara.

Calder Quartet in a “Quarantine Style” Performance

With works by Cage, Stravinsky, Ockeghem interspersed with arrangements by Kurtág, and Beethoven to reflect on the new and old.

Sunday June 14th Virtual Concert

Press Play; Click Box Above to Go Full Screen [ ]

Concert Notes

STEVE REICH (b. 1936)

Drumming (1971)

A Concert for Ojai: Pulses and Patterns

The 2020 Ojai Music Festival programs designed by Matthias Pintscher have alluded to numerous threads and connections, bridges and transitions — all resulting in the enticingly varied menu of today’s scene. We’ve encountered a mixture of leading European and American composers, reflected on Pierre Boulez and his ties to the natural setting of Ojai, and sampled from the legacy of figures from the post-Boulez generation like Olga Neuwirth, Unsuk Chin, and Pintscher himself. The music of Steve Reich completes this summer of creative juxtapositions — and fills in a missing link between the realms of European and American musical innovation.

But first, we turn to a pair of pieces by two other contemporary composers to start off this Concert for Ojai. Based in her native Mexico City, where she grew up in a family devoted to the traditions of Mexican folk music, Gabriela Ortiz explores intersections between the realms of avant-garde, jazz, and folk. Her opera Camelia La Tejana: Only the Truth was presented by Long Beach Opera in 2013. Written to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Cuarteto Latinoamericano, Lío de 4 is a brief and playful piece that focuses on the potential of rhythmic elegance and vitality.

A generation younger and a native of Puerto Rico, Brooklyn-based Angélica Negrón is a composer and multi-instrumentalist who has received accolades for her idiosyncratic use of toys, electronics, and robotic instruments. One of her current projects, for National Sawdust, is Chimera, a work-in-progress she describes as “a lip sync opera for drag queen performers and chamber ensemble exploring the ideas of fantasy and illusion as well as the intricacies and complexities of identity.”

Triste Silencio Programático (2002) is one of Negrón’s first compositions and was inspired by the 1920 silent film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari as well as by the aesthetic of German Expressionist cinema. Directed by Robert Wiene and written by Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer, Dr. Caligari involves “an insane hypnotist [who] uses a somnambulist to commit a series of crimes,” the composer explains. “At that time, I played violin and Celtic harp in a band called Sinestesia and one of our earliest gigs was to compose and perform a live score to go along with this film.”

Triste Silencio Programático draws on some of the themes she wrote for this score. “The first movement focuses on the dark mood of the film as well as the visual style with its unusual angles and distorted sets,” writes Negrón. “The second movement examines the dramatic contrast between light and shadow, while the third movement explores the destabilized characters and their inner mind with their complex psychological states. Triste Silencio Programático is a piece of music in black and white.”

It was during the 1966 Summer Festival (programmed by Ingolf Dahl) that Steve Reich’s music made its Ojai debut: Michael Tilson Thomas played his Two Fugues for Piano. By an ironic coincidence, Boulez paid his first visit to Ojai that same year. His inaugural season as music director followed in 1967, and Boulez would return over the span of nearly four decades as music director at Ojai more often than any other artist. Yet he had a blind spot for major contemporary American composers. Dismissive of Minimalism in general, he never programmed any Reich. Yet the Ensemble intercontemporain, founded by Boulez himself, would later commission Reich and won his admiration for its precision perfection in interpreting his music.

Completed in 1971 after a year of work, Drumming is one of the acknowledged early masterpieces of Minimalism and a pivotal work in Reich’s development. On the surface, it must have seemed far removed from the concerns of Boulez and his fellow avant-gardists in Western Europe — with the exception of György Ligeti. Reich once referred to Ligeti as “the European composer who has best understood both American and non-Western music.”

Reich’s teenage love of jazz — in particular, Kenny Clark’s artists with the Modern Jazz Quartet — led him to take up percussion and form his own band. In 1970, a few years after his breakthrough experiment with phase music [see sidebar], Reich traveled to Ghana to study the indigenous drumming traditions of the Ewe people. Ligeti would follow his lead in the next decade, similarly drawing inspiration from African sources.

Through close study with a master drummer of the Ewe tribe in Accra and his daily recording of lessons, Reich familiarized himself with the patterns and structures of African drumming. The most important influence of his stay in Africa, according to the composer, is that “it confirmed my intuition that acoustic instruments could be used to produce music that was genuinely richer in sound than that produced with electronic instruments.” Upon his return to the United States, he composed Drumming, which was premiered by the Steve Reich Ensemble at the Museum of Modern Art (in the film theater) in New York City in 1971.

Depending on the number of repeats that are played in performance, Drumming lasts between 55 and 75 minutes and is Reich’s longest composition. His unusual scoring calls for four tuned bongo drums, three marimbas, three glockenspiels, and piccolo, plus an alto and a soprano; whistling is also part of the soundscape, contributed by one of the singers or a percussionist. Reich recalls that the long decay of the marimba is what suggested the idea of incorporating women’s voices, which sing the “sub-patterns” that result acoustically from this resonance. He also compares the vocal patterns to Ella Fitzgerald’s style of scat singing, which he listened to often while exploring jazz in his early years. A similar process results in the whistling and piccolo patterns in the glockenspiel and final ensemble sections.

Notice the absence of bass instruments — in fact, the first three parts of the four-part work spiral successively upward in timbre until all of the forces join together in the fourth and final part. The whole work is shaped from a single core pattern. As Reich describes it: “Drumming begins with two drummers building up the basic rhythmic pattern of the entire piece from a single drum beat, played in a cycle of twelve beats with rests on all the other beats. Gradually, additional drumbeats are substituted for the rests, one at a time, until the pattern is completed. The reduction process is simply the reverse, where rests are gradually substituted for the beats, one at a time, until only a section leads to a build-up for the drums, marimbas, and glockenspiels simultaneously.”

—Thomas May

[SIDEBAR] Phase Music

In the mid-1960s, Reich experimented with material he taped from an African American San Francisco street preacher named Brother Walter. He lined up identical loops taped live from Brother Walter’s fire-and-brimstone speech-song commentary on Noah and the Flood and played them back on two cheap machines. By accident, the machines grew slightly out of sync with each other as they continued playing from the same starting point. This overlapping echo created fascinating rhythmic patterns in which the identical strands slowly separated as they went out of phase and then came together again in cycles. By manipulating the phasing — multiplying the individual strands and so forth — Reich found that he could build a dense web that acquires a hallucinatory quality as it lifts the listener outside ordinary time.

STEVE REICH (b. 1936)

Tehillim (1981)

Fire, Metal, and Praise

A Hebrew title graces Tehillim, a landmark composition in Steve Reich’s long career. “Western music before 1750 and from Debussy onwards, as well as jazz and non-Western music, are the sources from which I’ve drawn almost everything,” Steve Reich once observed. Within the rich spectrum of those non-Western musical sources can be found Ghanaian drumming, Balinese gamelan, and the Sephardic music he encountered in the mid-1970s in Israel.

The last involved a fresh encounter with Reich’s own roots and has born fruit in numerous compositions that reflect on the meaning of Jewish tradition and philosophy. Tehillim, composed in 1980, is the first of these — and Reich’s first piece incorporating voices since the mid-1960s, when he experimented with taped material. Here, he scores for four female voices plus chamber ensemble (with voices, winds, and strings amplified).

Referring to the Biblical Psalms attributed to David, Tehillim literally means “praises,” Reich explains, adding that the word derives from the same three-letter Hebrew root as does “Hallelujah.” The work is divided into four parts based, respectively on these Psalms (Hebrew sources are followed by the equivalent Christian translations shown in parentheses): 19:2-5 (19:1-4), 34:13-15 (34:12-14), 18:26-27 (18:25-26), and 150:4-6.

“One of the reasons I chose to set Psalms as opposed to parts of the Torah or Prophets,” according to Reich, “is that the oral tradition among Jews in the West for singing Psalms has been lost. (It has been maintained by Yemenite Jews.) This meant that I was free to compose the melodies for Tehillim without a living oral tradition to either imitate or ignore.” Handclapping, rattles, tuned tambourines without jingles, and small pitched cymbals are the closest analogues he uses to instruments that would have made music in the Biblical period. “Beyond this, there is no musicological content to Tehillim. No Jewish themes were used for any of the melodic materials.” The rhythms of the texts suggest the musical rhythms.

For the first text, Reich implements a sequence of canons leading up to all four voices in canon on each of the text’s four verses. A transition on the drum leads to two- or three-voice harmony for Psalm 34, with English horn, clarinet, drums, and clapping interwoven into the texture. The attention to melody here is inspired by Reich’s experiences of Sephardic cantillation.

The third part (Psalm 18), a slow movement, is unusually chromatic and begins as a duet between two of the voices. Ending with Psalm 150, Reich recapitulates ideas from the first three parts, returning to the opening tempo, and ends with full ensemble for a setting of Halleluyah.

—Thomas May

Artist Bios

Steve Reich, Composer

Steve Reich was recently called “our greatest living composer” (The New York Times), “America’s greatest living composer.” (The Village VOICE), “…the most original musical thinker of our time” (The New Yorker) and “…among the great composers of the century” (The New York Times).. From his early taped speech pieces It’s Gonna Rain (1965) and Come Out (1966) to his and video artist Beryl Korot’s digital video opera Three Tales (2002), Mr. Reich’s path has embraced not only aspects of Western Classical music, but the structures, harmonies, and rhythms of non-Western and American vernacular music, particularly jazz. “There’s just a handful of living composers who can legitimately claim to have altered the direction of musical history and Steve Reich is one of them,” states The Guardian (London).

In April 2009 Steve Reich was awarded the Pulitzer prize in Music for his composition ‘Double Sextet’.

Performing organizations around the world marked Steve Reich’s 70th- birthday year, 2006, with festivals and special concerts. In the composer’s hometown of New York, the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM), Carnegie Hall, and Lincoln Center joined forces to present complementary programs of his music, and in London, the Barbican mounted a major retrospective. Concerts were also presented in Amsterdam, Athens, Brussels, Baden-Baden, Barcelona, Birmingham, Budapest, Chicago, Cologne, Copenhagen, Denver, Dublin, Freiburg, Graz, Helsinki, Los Angeles, Paris, Porto, Vancouver, Vienna and Vilnius among others. In addition, Nonesuch Records released its second box set of Steve Reich’s works, Phases: A Nonesuch Retrospective, in September 2006. The five-CD collection comprises fourteen of the composer’s best-known pieces, spanning the 20 years of his time on the label.

In October 2006 in Tokyo, Mr. Reich was awarded the Preamium Imperial award in Music. This important international award is in areas in the arts not covered by the Nobel Prize. Former winners of the prize in various fields include Pierre Boulez, Lucian Berio, Gyorgy Ligeti, Willem de Kooning, Jasper Johns, Richard Serra and Stephen Sondheim.

In May 2007 Mr. Reich was awarded The Polar Prize from the Royal Swedish Academy of music. The prize was presented by His Majesty King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden. The Swedish Academy said: “…Steve Reich has transferred questions of faith, society and philosophy into a hypnotic sounding music that has inspired musicians and composers of all genres.” Former winners of the Polar Prize have included Pierre Boulez, Bob Dylan, Gyorgi Ligeti and Sir Paul McCartney.

In December 2006 Mr. Reich was awarded membership in the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest and in April 2007 he was awarded the Chubb Fellowship at Yale University. In May 2008 he was elected to the Royal Swedish Academy of Music.

Born in New York and raised there and in California, Mr. Reich graduated with honors in philosophy from Cornell University in 1957. For the next two years, he studied composition with Hall Overton, and from 1958 to 1961 he studied at the Juilliard School of Music with William Bergsma and Vincent Persichetti. Mr. Reich received his M.A. in Music from Mills College in 1963, where he worked with Luciano Berio and Darius Milhaud.

During the summer of 1970, with the help of a grant from the Institute for International Education, Mr. Reich studied drumming at the Institute for African Studies at the University of Ghana in Accra. In 1973 and 1974 he studied Balinese Gamelan Semar Pegulingan and Gamelan Gambang at the American Society for Eastern Arts in Seattle and Berkeley, California. From 1976 to 1977 he studied the traditional forms of cantillation (chanting) of the Hebrew scriptures in New York and Jerusalem.

In 1966 Steve Reich founded his own ensemble of three musicians, which rapidly grew to 18 members or more. Since 1971, Steve Reich and Musicians have frequently toured the world, and have the distinction of performing to sold-out houses at venues as diverse as Carnegie Hall and the Bottom Line Cabaret.

Mr. Reich’s 1988 piece, Different Trains, marked a new compositional method, rooted in It’s Gonna Rain and Come Out, in which speech recordings generate the musical material for musical instruments. The New York Times hailed Different Trains as “a work of such astonishing originality that breakthrough seems the only possible description….possesses an absolutely harrowing emotional impact.” In 1990, Mr. Reich received a Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Composition for Different Trains as recorded by the Kronos Quartet on the Nonesuch label.

In June 1997, in celebration of Mr. Reich’s 60th birthday, Nonesuch released a 10-CD retrospective box set of Mr. Reich’s compositions, featuring several newly-recorded and re-mastered works. He won a second Grammy award in 1999 for his piece Music for 18 Musicians, also on the Nonesuch label. In July 1999 a major retrospective of Mr. Reich’s work was presented by the Lincoln Center Festival. Earlier, in 1988, the South Bank Centre in London, mounted a similar series of retrospective concerts.

In 2000 he was awarded the Schuman Prize from Columbia University, the Montgomery Fellowship from Dartmouth College, the Regent’s Lectureship at the University of California at Berkeley, an honorary doctorate from the California Institute of the Arts and was named Composer of the Year by Musical America magazine.

The Cave, Steve Reich and Beryl Korot’s music theater video piece exploring the Biblical story of Abraham, Sarah, Hagar, Ishmael and Isaac, was hailed by Time Magazine as “a fascinating glimpse of what opera might be like in the 21st century.” Of the Chicago premiere, John von Rhein of the Chicago Tribune wrote, “The techniques embraced by this work have the potential to enrich opera as living art a thousandfold….The Cave impresses, ultimately, as a powerful and imaginative work of high-tech music theater that brings the troubled present into resonant dialogue with the ancient past, and invites all of us to consider anew our shared cultural heritage.”

Three Tales, a three-part digital documentary video opera, is a second collaborative work by Steve Reich and Beryl Korot about three well known events from the twentieth century, reflecting on the growth and implications of technology in the 20th century: Hindenburg, on the crash of the German zeppelin in New Jersey in 1937; Bikini, on the Atom bomb tests at Bikini atoll in 1946-1954; and Dolly, the sheep cloned in 1997, on the issues of genetic engineering and robotics. Three Tales is a three act music theater work in which historical film and video footage, video taped interviews, photographs, text, and specially constructed stills are recreated on computer, transferred to video tape and projected on one large screen. Musicians and singers take their places on stage along with the screen, presenting the debate about the physical, ethical and religious nature of technological development. Three Tales was premiered at the Vienna Festival in 2002 and subsequently toured all over Europe, America, Australia and Hong Kong. Nonesuch is releasing a DVD/CD of the piece in fall 2003.

Over the years, Steve Reich has received commissions from the Barbican Centre London, the Holland Festival; San Francisco Symphony; the Rothko Chapel; Vienna Festival, Hebbel Theater, Berlin, the Brooklyn Academy of Music for guitarist Pat Metheny; Spoleto Festival USA, West German Radio, Cologne; Settembre Musica, Torino, the Fromm Music Foundation for clarinetist Richard Stoltzman; the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra; Betty Freeman for the Kronos Quartet; and the Festival d’Automne, Paris, for the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution.

Steve Reich’s music has been performed by major orchestras and ensembles around the world, including the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas, New York Philharmonic conducted by Zubin Mehta; the San Francisco Symphony conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas; The Ensemble Modern conducted by Bradley Lubman, The Ensemble Intercontemporain conducted by David Robertson, the London Sinfonietta conducted by Markus Stenz and Martyn Brabbins, the Theater of Voices conducted by Paul Hillier, the Schoenberg Ensemble conducted by Reinbert de Leeuw, the Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Robert Spano; the Saint Louis Symphony conducted by Leonard Slatkin; the Los Angeles Philharmonic conducted by Neal Stulberg; the BBC Symphony conducted by Peter Eötvös; and the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas.

Several noted choreographers have created dances to Steve Reich’s music, including Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker (“Fase,” 1983, set to four early works as well as”Drumming,”1998 and “Rain” set to “Music for 18 Musicians”), Jirí Kylían (“Falling Angels,” set to “Drumming Part I”), Jerome Robbins for the New York City Ballet (“Eight Lines”) and Laura Dean, who commissioned “Sextet”. That ballet, entitled “Impact,” was premiered at the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival, and earned Steve Reich and Laura Dean a Bessie Award in 1986. Other major choreographers using Mr. Reich’s music include Eliot Feld, Alvin Ailey, Lar Lubovitch, Maurice Bejart, Lucinda Childs, Siobhan Davies and Richard Alston.

In 1994 Steve Reich was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, to the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts in 1995, and, in 1999, awarded Commandeur de l’ordre des Arts et Lettres.

Sunday Playlist

Sunday, June 14, 2020 | 8:30-9:30am

Libbey Bowl

MATTHIAS PINTSCHER 4° quartetto d’archi (“Ritratto di Gesualdo”)

Calder Quartet

SALVATORE SCIARRINO Gesualdo senza parole (a 400 anni dalla morte)

I. Libro III: XI. “Non t’amo“

II. Libro XIV: XI. “Sparge la morte”

III. Libro VI: I. “Se la mia morte brami”

IV. Libro VI: II. “Beltà poi che t’assenti”

Ensemble intercontemporain (EIC)

Matthias Pintscher conductor

J.S. BACH Contrapunctus Nos. 1, 3, 4, and 9 from The Art of the Fugue, BWV 1080

Calder Quartet

PIERRE BOULEZ Mémoriale (…explosante-fixe… Originel)

EIC

Matthias Pintscher conductor

Sunday, June 14, 2020 | 11:00am-12:30pm

Libbey Bowl

EDGARD VARÈSE Octandre

I. Assez lent

II. Trèsvif et nerveux

III. Grave-Animé et jubilatoire

Ensemble intercontemporain (EIC)

FRANK ZAPPA The Perfect Stranger

EIC

Matthias Pintscher conductor

GUSTAV MAHLER Das Lied von der Erde (arr. Glenn Cortese)

Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde” (“The Drinking Song of Earth’s Sorrow”)

Der Einsame im Herbst (“The Solitary One in Autumn”)

Von der Jugend (“Of Youth”)

Von der Schönheit (“Of Beauty”)

Der Trunkene im Frühling (“The Drunkard in Spring”)

Der Abschied (“The Farewell”)

Tamara Mumford mezzo-soprano

Andrew Staples tenor

EIC

Matthias Pintscher conductor

GABRIELA ORTIZ Lío de 4

ANGÉLICA NEGRÓN Triste Silencio Programático

Calder Quartet

STEVE REICH Tehillim

(Spotify Playlist)

(Apple Music)

LA Phil New Music Group

Paolo Bortolameolli conductor

STEVE REICH Drumming

Percussion All Stars

Saturday June 13th Virtual Concert

Press Play; Click Box Above to Go Full Screen [ ]

Concert Notes

JOHN CAGE (1912-1992)

String Quartet in Four Parts (1950)

Seasons of the Sublime

In 1946, just one year before the Ojai Music Festival was founded, John Cage had a life-changing encounter with the Indian singer and tabla player Gita Sarabhai. “She was concerned about the influence Western music was having on traditional Indian music, and she’d decided to study Western music for six months with several teachers and then return to India to do what she could to preserve the Indian traditions,” Cage wrote. He offered to teach her for free if she would in turn help him understand Indian music.

The mutual exchange left a profound mark on Cage, who was coping with personal crisis during these years. When Sarabhai introduced him to the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, the effect was so powerful that it “took the place of psychoanalysis,” he remarked. Cage recalled that from Sarabhai he learned that “the purpose of music is to sober and quiet the mind, thus making it susceptible to divine influences.” Along with aesthetic and metaphysical ideas from Hinduism, Cage also continued to explore his ongoing interest in Zen Buddhism and its concepts of silence and mindfulness.

The Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano explored what Cage called the “‘permanent emotions’ of Indian tradition … and their common tendency toward tranquility.” He turned to the Hindu understanding of the annual cycle in his 1947 ballet The Seasons (with Lou Harrison contributing his efforts as an orchestrator). In String Quartet in Four Parts, composed between 1949 and 1950 and dedicated to Harrison, Cage again used the cycle of seasons as understood in Hinduism as a framework, tracing the phases of creation, preservation, destruction, and quiescence (which are associated with spring, summer, fall, winter, respectively).

Cage traveled to Europe in 1949 — where he met and was initially championed by Pierre Boulez — and started composing the quartet while in Paris during the summer: hence, the work begins with the season of “preservation.” The tempo seems to slow down gradually to near stasis for the third part (winter) and then suddenly quickens for the season of creative renewal, spring.

But within this familiar, four-movement context, Cage’s sound world is alien and often bewildering. The material comprises a kind of palette (Cage called it a “gamut”) of previously organized, fixed sonorities, each of which remains unchanged each time it recurs. The light touch and lack of vibrato he requests result in a weirdly archaic, not-quite-early-music sound.

If such austere melodies generate an aura of calm illumination, Matthias Pintscher’s Uriel is “about resonances, about the inward and outward givens of existence, about life itself,” as he observes. Hebrew titles are found throughout his oeuvre — as with bereshit and nur, both of which would have already been performed at this year’s Festival — though Uriel is also recognized in English as one of the principal figures in the hierarchy of angels — described by Milton as the “sharpest sighted spirit in all of Heaven” and cast as a tenor narrator in Haydn’s Creation.

The Hebrew word itself means “light of God.” The archangel Uriel is additionally associated with “God’s fire,” the sun, illumination, and artistic inspiration. Pintscher wrote Uriel in 2011-12 but later made it the final panel in a chamber triptych he calls Profiles of Light. The cycle begins with Now I, a work for solo piano in homage to his great mentor Pierre Boulez on his 90th birthday, and Now II for solo cello (both from 2015).

The names of all three pieces derive from the work of the American abstract expressionist Barnett Newman. His essay The Sublime Is Now points to the ways in which American abstract artists “free from the weight of European culture” (in 1947) reassert the “natural desire for the exalted.”

Pintscher, an avid collector of visual art, was especially drawn to the essence Newman distills in his painting Uriel (1955): “The closer Newman got to death, the more luminous his work became,” he says. Pintscher chose the cello as a highly suitable instrument for depicting such existential conditions” — mediating between the inward and outward illumination signified by the angel.

Following Cage’s elate stasis and Pinscher’s exquisite, visionary dialogue between cello and piano, Charles Ives’s Second String Quartet stages a stunning range of confrontations. The composer supplied a terse program of his own: “Four men — who converse, discuss, argue (in re ‘Politick’), fight, shake hands, shut up — then walk up the mountainside to view the firmament.” Along the way, their discourse is a far remove from Goethe’s “conversation between four reasonable, intelligent people.”

Annoyed by what he perceived as the affected refinement of the classical European tradition of quartet playing, Ives produced one of his most challenging, most maverick creations in the Second Quartet. He composed it between 1911 and 1913 but drew on earlier material; the work was not premiered until 1946 at Juilliard.

Woven into the score as expected with Ives, is an abundance of musical quotations, both vernacular American tunes and the flotsam of Old World tradition (Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy”) — all set against a sinewy atonal background. The final, transcendent movement in particular sets a snippet from Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique against “Nearer My God to Thee.”

—Thomas May

Artist Bios

Calder Quartet

Benjamin Jacobson, violin

Tereza Stanislav, violin

Jonathan Moerschel, viola

Eric Byers, cello

Hailed as “Superb” and “imaginative, skillful creators” by the New York Times, the Calder Quartet captivates audiences exploring a broad spectrum of repertoire, always striving to fulfill the composer’s vision in their performances. The group’s distinctive artistry is exemplified by a musical curiosity brought to everything they perform and has led them to be called “one of America’s most satisfying – and most enterprising – quartets”. (Los Angeles Times)

Winners of the prestigious 2014 Avery Fisher Career Grant, they are widely known for the discovery, commissioning, recording and mentoring of some of today’s best emerging composers. In addition to performances of the complete Beethoven and Bartok quartets, the Calder Quartet’s dedication to commissioning new works has given rise to premieres of dozens of string quartets by established and up-and-coming composers including Peter Eötvös, Andrew Norman, Christopher Rouse, Ted Hearne and Christopher Cerrone. Inspired by innovative American artist Alexander Calder, the Calder Quartet’s desire to bring immediacy and context to the works they perform creates an artfully crafted musical experience.

Recent highlights include Carnegie Hall, Kennedy Center, Disney Hall, Lincoln Center, Metropolitan Museum of Art, multiple performances at Wigmore Hall, Barbican, Salzburg Festival, Donaueschingen Festival, Frankfurt Alte Oper, Tonhalle Zurich, IRCAM Paris, Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie and the Sydney Opera House. They have performed as soloists with the Cleveland Orchestra and LA Philharmonic and have collaborated with musicians such as Thomas Adès, Peter

Eötvös, Anders Hillborg, Daniel Bjarnasson, Andrew Norman, Audrey Luna, Johannes Moser, Joshua Bell, Menahem Pressler, Joseph Kalechstein, Paul Neubauer, Iva Bittová and Edgar Meyer. In 2017, the Calder Quartet signed an exclusive, multi-disc record deal with Pentatone with their debut recording featuring Beethoven scheduled for release in Fall 2018.

The quartet has signed an exclusive, multi-disc record deal with Pentatone records. Their debut recording features the music of Beethoven and Swedish composer Anders Hillborg. Previously the quartet has appeared on Signum Classics, BMC records, Bridge Records and E1 recording the quartets of Peter Eötvös with Audrey Luna, Thomas Adès’ chamber music with the composer at the piano, early works of Terry Riley, the chamber music of Christopher Rouse, Mozart Piano concertos with Anne-Marie McDermott, and Ravel and Mozart quartets.

As a side project, the quartet has collaborated with acts such as Andrew WK, Lord Huron, Vampire Weekend, and The National. Television appearances include the Late Show with David Letterman, Tonight Show with Jay Leno, Tonight Show with Conan O’Brien, Late Night with Jimmy Kimmel, and the Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson as well as radio appearances on KCRW’s Morning Becomes Eclectic, Performance Today, WQXR New York, KUSC Los Angeles, Colorado Public Radio, and NPR.

In 2011 the Calder Quartet launched a non-profit dedicated to furthering its efforts in commissioning, presenting, recording, and education, collaborating with

the Getty Museum, Segerstrom Center for the Arts, and the Barbican Centre in London. The Calder Quartet formed at the University of Southern California’s Thornton School of Music and continued studies at the Colburn Conservatory of Music with Ronald Leonard, and at the Juilliard School, receiving the Artist Diploma in Chamber Music Studies as the Juilliard Graduate Resident String Quartet. The quartet regularly conducts master classes and has taught at the Colburn School, the Oberlin School the Juilliard School, Cleveland Institute of Music, University of Cincinnati College Conservatory and USC Thornton School of Music.

Saturday Playlist

Saturday, June 13, 2020 | 8:00-9:15am

Zalk Theater, Besant Hill School

JOHN CAGE String Quartet in Four Parts

1. Quietly Flowing Along

2. Slowly Rocking

3. Nearly Stationary

4. Quodlibet

Calder Quartet

MATTHIAS PINTSCHER Uriel

Eric Byers cello

Kevin Kwan Loucks piano

CHARLES IVES String Quartet No. 2 (Calder)

1. Discussions (Andante moderato-Andante con

spirito-Adagio molto)

2. Arguments (Allegro con spirito)

3. The Call of the Mountains (Adagio-Andante-Adagio)

Calder Quartet

Saturday, June 13, 2020, 2020 | 11:00am – 12:30pm

Libbey Bowl

GYÖRGY LIGETI Concerto for Piano and Orchestra

Ensemble intercontemporain (EIC)

Hidéki Nagano piano

Matthias Pintscher conductor

J.S. BACH Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G Major, BWV 1049

Ojai Music Festival Ensemble

Saturday, June 13, 2020 | 7:30-8:00pm

Libbey Bowl

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART Serenade in B-flat Major, K. 361/370a (“Gran Partita”)

Members of the Los Angeles Philharmonic

Friday June 12th Virtual Concert

Press Play; Click Box Above to Go Full Screen [ ]

Concert Notes

OLGA NEUWIRTH (b. 1968)

Eleanor (2014-15)

The creative act of imagining beginnings can also take a critical turn, driven by the urge to call attention to what has gone wrong. The legacy Eleanora Harris Fagan (professionally known as Billie Holiday) has been enshrouded in romanticizing myth that blots out memories of the racism she endured and that countless others still endure. Olga Neuwirth looks back to the reality she faced, as an African-American artist and woman. Her suffering is bridged by the unacceptable truth that more than 50 years after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. (in 1968, the year in which Neuwirth was born), the “shameful conditions” that King denounced in his final speech have persisted.

Eleanor, writes Neuwirth “is a tribute to all those who have dared and still dare to voice criticism despite social and political opposition. In our oh-so-worldly times, when even faint dissent is seen as a threat, fingers are scandalously quick to pull triggers. Eleanor would, however, especially like to pay tribute to courageous women — which explains the woman’s name in the title. Here the spotlight is on the many forgotten female African-American jazz musicians from the era ‘when men ruled the beat.’”

Neuwirth’s encounters with racism and sexism during her various stays in the United States forced her to confront the intense contradictions at the root of American society. Its vibrant cultural pluralism — a signature of Eleanor and of Neuwirth’s music in general — attracted her: even as a youngster studying trumpet back in her native Austria, Neuwirth dreamed of following in the footsteps of Miles Davis. Her father was, in fact, a jazz pianist. In 2006, in pre-Obama America, she embarked on American Lulu, a radical new take on Alban Berg’s unfinished opera Lulu. Neuwirth set the story in the Civil Rights era, incorporating speeches from King as well as the poetry of June Jordan to dramatize the courage of those resisting systemic racism and discrimination against women.

Eleanor, commissioned by the Salzburg Festival, premiered in 2015, with Della Miles creating the title role as “blues singer” and Tyshawn Sorey on percussion. Neuwirth adapted material from the third act of American Lulu for Eleanor, which, as the composer explains, “tries to mount a kind of accusation from the standpoint of one person alone. Without giving the perpetrators a voice, Neuwirth develops a structure in which “the woman’s voice is surrounded and symbolically encouraged” by narrations from King’s speeches and Jordan’s poetry. The drum-kit player also becomes her “ally.” Neuwirth provides further commentary:

“Beginning in child, [Eleanor/Billie Holiday’s] life was marked by abuse, which left deep wounds. Wounds that made it difficult to live. Her great talent and the enormity of her soul and spirit were thus constantly fighting a sense of emptiness. Nothing was able to dull her profound nihilism.

Which is why I have replaced the cultivated aura of classical song with the directness of the blues. Eleanor insists on the irrevocability of pain and her own subjectivity. She struggles for freedom, treading a difficult path, yet one she has chosen. Despite the abuse, she self-confidently seeks her own form of expression, her own identity. Music and text have been conceived to unleash an unrelenting maelstrom. The musical form should exude a spontaneity that is not, as so often in ‘contemporary classical’ music, obstructed by structural limitations. Eleanor begins like a review of old blues records in the tradition of Williams, Lambert and Hendricks: with quasi instrumental jazz vocals — transformed by means of percussion, electric piano, and electric guitar into an illusory now.

Eleanor was a spontaneous expression of my helplessness and outrage at the racist violence and bloodshed committed in the editorial offices of Charlie Hebdo. I could not and did not want to remain silent. After the initial shock, the time had come to find the courage to reflect. The piece was already almost finished, but I did not want to let the heat of that moment dissipate, because doing so would not, as we have so often been told, lead automatically to a more balanced truth. I wanted to react right away and not later, when everything had ‘settled’ down.

OLGA NEUWIRTH (b. 1968)

Aello – ballet mécanomorphe (2017)

Swerving in and out of Time

In a beautiful obituary she wrote for Pierre Boulez in 2016, Olga Neuwirth recalls being captivated by his “musical personality” while still a teenager growing up in the Austrian provinces. She found inspiration not only in his music but in Boulez’s “uttermost conviction that we are living in the here and now and that we must think and write music accordingly, while countering cynicism and indifference.”

How does the endeavor to write music that acknowledges our “living in the here and now” play out in a context that’s as self-conscious about traditions and historical connections as classical music? The program Matthias Pintscher has designed for this concert presents examples both by Neuwirth and by György Ligeti, another leading figure of the Boulez generation whose music shares her spirit of unpredictable imagination and fondness for what the absurd can disclose. The idea of the concerto itself, around which this program revolves, ranks among the most enduring genre conventions in classical art music — and has proved to be inexhaustible precisely through the innovations, the infusion of the “here and now,” by composers such as Neuwirth and Ligeti.

In the wake of his sole opera Le Grand Macabre (he called it an “anti-anti-opera”), which premiered in 1978, Ligeti — always skeptical of dogma and systematic approaches — endured a creative dry spell during which he struggled with finding his way forward. The Jewish-Hungarian composer ceased to produce any significant new works, though he continued making, as he put it, “hundreds of sketches, only to abandon them.” During this period, he was hard at work on a commission for a piano concerto. Its genesis cost enormous creative toil — and opened the way to a way out of his dilemma.

By the 1980s, the postwar avant-garde’s utopian idealism had mostly faded, while the emerging ideology of post-modernism seemed, to Ligeti, to encourage a reactionary if not cynical stance of bad faith: this was the past recuperated as commodity. Ligeti did refocus his lens on the past, but with characteristic originality and quirkiness, in ways that are thrillingly unsettling. His Horn Trio of 1982, for example, is an explicit homage to the template Brahms created, while at the same time a creative swerving from the source (to borrow the literary critic Harold Bloom’s term).

Ligeti meanwhile persevered in several stages with the Piano Concerto. After unveiling his first version in the traditional three-movement format in 1986, he concluded that it “demanded continuation” and added two more movements, with the fourth now serving as the conceptual center of the whole work. This final version was first performed in 1988. Ligeti considered the result no less than a statement of his “artistic credo” showing his “independence from criteria of the traditional avant–garde, as well as the fashionable postmodernism.”

The Piano Concerto realizes what Ligeti called “new concepts of harmony and rhythm.” One of his students, the Puerto Rican composer Roberto Sierra, sparked his fascination with different kinds of rhythmic complexity from Latin American and African cultures. These impulses set the stage in the opening movement, in which Ligeti splits the ensemble into two parts, each playing a different meter. The Concerto exploits “illusory rhythmics and illusory melody,” as Ligeti defines the trompe l’oreille effects of individual layers that, in concert, cause us to hear patterns that are not actually written in the score. Similarly, Ligeti is fond of tricking the ear with counterintuitive instrumentation (high instruments playing in low register and vice versa) and unexpected sounds from the ocarina and slide whistle.

Still another inspiration comes from the ground shared between science and art — which is the case for Neuwirth as well. Ligeti delighted in computer simulations of the Julia and Mandelbrot fractal sets. The fourth movement emulates such “self-similar” structures on a poetic level — becoming a metaphor for the general principle of remaking and renewing the past, what is given, in the here and now: “always new but however of the same,” per Ligeti. Overall, the Piano Concerto represents his “main intention as a composer”: to convey “the spell of time, the enduring its passing by, closing it in a moment of the present.”

Olga Neuwirth’s Aello – ballet mécanomorphe originated as part of the “Bach Brandenburg Project” commissioned by the Swedish Chamber Orchestra and the Danish conductor Thomas Dausgaard. The project set out to present a contemporary counterpart to the group of six concertos that J.S. Bach presented in 1721 to the Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt (half-brother of Friedrich I of Prussia). Neuwirth was assigned to respond to Brandenburg Concerto No. 4. (The other five composers include Uri Caine, Brett Dean, Anders Hillborg, Steven Mackey, and Mark Anthony Turnage.)

Bach’s revered collection was apparently never even heard by their namesake, who lacked the richly varied musical resources and virtuoso musicians needed to realize them. Familiar as they have become, the Brandenburg Concertos themselves subvert and interrogate the conventions that had grown up around what was then the still-young genre of the Baroque concerto in three movements (fast-slow-fast). While the concertmaster had emerged as the expected virtuoso soloist for a concerto, “a whole concerto is now to be dominated by two violas, or two flutes, or even by the harpsichord,” notes Dausgaard. “Hierarchy has been dissolved and an alternative world-order presented.”

No. 4 in G Major is scored for strings and continuo and three soloists: violin and a pair of fiauti dolci or flauti d’echo (possibly treble recorders) — a much-debated phrase whose interpretation played a key role in Neuwirth’s choice of instrumentation for her new work. The outer movements behave like a chamber violin concerto, as Bach assigns much virtuosity to the solo violin, with its two wind companions offering encouragement.

Premiered in 2018, Aello – ballet mécanomorphe at first suggests a direct bridge between the musical past and the “here and now” — Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 is, after all, its model, formally and thematically as well as in terms of instrumentation. Yet Neuwirth “swerves” from all of these parameters in wonderfully unexpected ways. Investigating what Bach may have meant by fiauti d’echo, she found a strange double-pipe instrument that led to the idea of using a pair of muted trumpets — one regular, one piccolo. (The trumpet was Neuwirth’s instrument growing up.) In another identity transformation, she turns the violin, with its leading role, into a “super-flute,” originally tailored to the virtuosa and new music champion Claire Chase. The part, which calls for flute and, in the final movement, brass flute, involves a repertoire of unusual tone productions, attacks, and even jet whistling.

Neuwirth also transforms the soundscape of the continuo, whose function in Bach is to provide harmonic scaffolding. Intrigued by a phrase (attributed to the French writer Colette) that Bach sounds like “a celestial sewing machine,” she makes the harpsichord into a multiple-personality small band of its own comprising a subtly amplified, classic Olivetti Lettera 22 typewriter, a reception bell, a water-filled glass, a mechanical milk frother, and a synthesizer.

These “modern mechanicals” in turn are evoked by the Dadaist subtitle (worthy of Ligeti), a “ballet in the form of a machine.” Aello, by contrast, is a mythic-poetic allusion to one of the three ancient Greek Harpies associated with storms, who would torment victims while leading them to the Underworld. That, however, is her reputation from a biased male perspective. In Neuwirth’s view, Aello is “someone sent by the gods to restore peace, if necessary with force, and to exact punishment for crimes.” Similarly, the “macho” personae of Baroque trumpets is tamed and, well, Dada-fied through muting. The entire ensemble and trio of soloists, meanwhile, are tuned to four different pitches.

While echoes of the Bach source clearly emerge, they do so in the way dreams are recalled. What may sound at one point like carnivalesque parody suddenly swerves into the “celestial” and mysterious — and the uncanny. The flute-goddess walks a tightrope, leading us along a path that touches on childhood memories, cultural ambiguity, and fresh-eyed wonder.

Eleanor is my way of showing solidarity and protesting artistically against the daily pressures to conform, and against external and internal repression.

Eleanor Text

Musicians: Start running cuz this life is hell!

Eleanor: I’ll run so fast till someone wakes me up cuz evil spirits are all around my legs.

I was looking out at the rain:

Why did you wanna do all these mean things to me?

Why did you wanna do,

Why did you wanna do all these things to me?

I began to fall so low –

I didn’t have a friend and no place to go

Nobody knows you

When you’re down and out.

Am not like a turtle, can’t hide underneath a hard shell.

Peace for my heart!

Born under a bad sign

I’ve been blue since I remember

I feel so low

cuz nobody wants me around their door

So: ev’ry day I’ve the Blues.

Bad luck and trouble is my only friend

I’ve been on my own since I was twelve

And my whole life has been one big fight.

I wish I could see cuz am so sick and tired of being in misery.

Now listen to my tale which, sadly, is true:

They’ve destroyed my dignity.

All they said never meant a thing. I remember the promises they’ve made me.

They played with me on purpose. Hence I feel so low.

Well, I’m not pliable enough, I see.

Too bad words seemed so logical. –

Like always, no reaction.

Power depersonalizes ev’rything, claiming experiences are universal-

But: we all think differently.

I don’t think we are capable of tolerance, but rather full of hate, contempt and hypocrisy.

My openness only fuels misunderstandings, cuz you all find me repulsive.

Why can’t you just be honest? –

But you all can’t kill my free spirit! I’ve had it since I was young. Even wrote my own songs

back then. True I’m a strange person, but I never denied myself totally.

I’ve finally found myself again. But: I’ll never forget what you have done.

Samples:

Sample 2

June Jordan: First section of “Rape Is Not a Poem”. In: Passion: New Poems (1977-1980)

One day she saw them coming into the garden

where the flowers live.

The found the colors beautiful and

they discovered the sweet smell

that the flowers held

so they stamped upon and tore apart

the garden

just because (they said)

those flowers?

They were asking for it.

Sample 4:

June Jordan

There is nothing left but drippings

of power and

a consummate wreck of tenderness

I want to know:

Is this what you call

Only Natural?

Sample 5

Martin Luther King Jr. : Adapted and abridged from “The Rising Tide of Racial Consciousness” (1960)

One of the sure signs of maturity is the ability to rise to the point of self-criticism. Some of us have become cynical and disillusioned. Some have so conditioned themselves to the system of segregation that they have lost that creative something called initiative. Many of us live above our means, spend money on non-essentials and frivolities, and fail to give to serious causes, organizations, and education institutions that so desperately need funds. Therefore there is a pressing need to develop a positive program through which these standards can be improved.

Sample 6

Martin Luther King Jr. : Adapted and abridged from “The Only Road to Freedom” (1966)

There is no easy way to create a world where men and women live together, where each has his own job and house and where children receive as much education as their minds can absorb. If such a world is created in our lifetime, it will be done by people of good will.

It will be done through massive protest and by rejecting the racism, materialism and violence that has characterized Western civilization and especially by working toward a world of brotherhood, cooperation and peace.

Sample 7

Martin Luther King Jr.

Love MUST be at the forefront of our movement if it is to be a successful movement. And when we speak of love, we speak of understanding, good will toward ALL men. In struggling for human dignity we must not succumb to the temptation of becoming bitter or indulging in hate campaigns. We have learned through the grim realities of life and history that hate and violence solve nothing. At the end it is only destructive for everybody.

Sample 8

Martin Luther King Jr. : Adapted and abridged from “The Current Crisis in Race Relations” (1958)

We also revolt against what I often call the myth of time. There are those who say wait for time and time will solve the problem. The people who argue this do not themselves realize that time is neutral, that it can be used constructively or destructively. This movement is based on hope. But before the victory is won, some will lose jobs, some will be called communists, and reds, merely because they believe in brotherhood. Some will be dismissed as dangerous rabble rousers and agitators merely because they’re standing up for what is right, but we shall overcome.

Sample 9

Martin Luther King Jr. : Adapted and abridged from “The Current Crisis in Race Relations” (1958)

But there are some things in our social system to which all of us ought to be maladjusted. I never intend to adjust myself to the viciousness of mob rule. I never intend to adjust myself to the evils of segregation and the crippling effects of discrimination. I never intend to adjust myself to the inequalities of an economic system which takes necessities from the masses to give luxuries to the classes. I never intend to become adjusted to the madness of militarism and the self-defeating method of physical violence. The world is in desperate need of such maladjustments to bring a daybreak of freedom and justice.

Sample 10

Martin Luther King Jr. : Adapted and abridged from his last speech, “I See the Promised Land” (1968)

That’s what the whole movement is about: we aren’t engaged in any negative protest and in any negative argument with anybody. We are saying that we are determined to be men. We are determined to be people/ We are saying that we are God’s children. And that we don’t have to live like we are forced to live.

I don’t know what will happen now. I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Now we’re going to march again, and we’ve got to march again, in order to put issue where it is supposed to be.

–

”Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness light a mighty stream”.

Remembering the vision, courage and lasting endurance of Martin Luther Kink and in memoriam Elsa Cayat

Artist Bios

Olga Neuwirth, Composer

Olga Neuwirth was born in Graz, Austria, in 1968.

She studied at the Academy of Music in Vienna and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. During her stay in the States she also attended an art college, where she studied painting and film. Her private teachers in composition included Adriana Hölszky, Tristan Murail and Luigi Nono. She first burst onto the international scene in 1991, at the age of 22, when two of her mini-operas were performed at the Wiener Festwochen. Ever since her works have been presented worldwide.

In 1998 she was featured in two portrait concerts at the Salzburg Festival within the framework of the Next Generation series. The following year, her music theatre work Bahlamms Fest, with a libretto by Elfriede Jelinek, premiered at the Wiener Festwochen and won the Ernst Krenek prize. A year later, she wrote Clinamen/Nodus for Pierre Boulez and the London Symphony Orchestra tour. In 2002 Olga was appointed composer-in–residence at the Lucerne Festival.

With Nobel Prize winning novelist Elfriede Jelinek she has created two radio plays and three operas.

Her opera Lost Highway, based on the film by David Lynch, premiered in 2003 and won a South Bank Show Award for the production presented by English National Opera at the Young Vic in 2008.

Since Olga Neuwirth was a teenager, she has also been interested in film, literature, architecture and the visual arts. Aside from composing, she also realises sound installations, art exhibitions and short films and has written several articles and a book; one of her multi-media installations was presented at the documenta 12 in Kassel in 2007.

Olga Neuwirth’s works are multi-layered and multi-sensory. Some pieces also draw on the full range of effects of both electronic and orchestral instruments as well as video, which she began integrating into some of her works in the late 1980’s. The listener is struck by the immediacy of her music, which is often dramatic and expressive as she is particularly interested in emotions and how they relate to the brain and memory.

Many recordings of her music have been released on the label Kairos.

In 2008 she was awarded the Heidelberg Artist Prize. In 2010, as the first woman ever in the category of music, she received the Grand Austrian State Prize as well as the Louis Spohr Prize of the City of Braunschweig

In 2012 Olga Neuwirth completed two new operas while living in NYC: The Outcast on Hermann Melville, and American Lulu, a version of Alban Berg’s Lulu which was premiered in Berlin and subsequently given a new production in Bregenz, Edinburgh and London in 2013 and then in Vienna in 2014. In early 2015 she completed a film score for a silent film and a feature film by Franz/Fiala, and the orchestral work Masaot/Clocks without hands for the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. It was premiered in Koeln and Vienna in May and had it’s US premiere in February 2016 at Carnegie Hall under the baton of Valerij Gergjev.

At the Salzburg Festival her Eleanor Suite for Bluessinger, drum-kit-player and ensemble was premiered in August 2015. Her 80 minutes electronic/space/ensemble piece Le Encantadas based on the acoustics of a venetian church received its premiere at Donaueschingen and at the Festival d’Automne à Paris with further performances in 2016 and 2017. She received the prestigious Roche Commission for the Lucerne Festival in 2016 for her percussion concerto Trurliade–Zone Zero and was composer-in-residence at the festival for the second time.

In march 2017 her 3D sound-installation in collaboration with IRCAM was inaugurated at Centre Pompidou in Paris for it’s 40th anniversary.

In 2017 she has collaborated with architect Peter Zumthor and Asymptote Architects.

Beside several concerts for her 50th anniversary in 2018, Lost Highway and The Outcast can be seen in new productions. Lost Highway under the direction of Yuval Sharon and The Outcast under Netia Jones.

Her new opera Orlando premiered at the Wiener Staatsoper in 2019.

Matthias Pintscher, Music Director

“It is a tremendous pleasure and incredible honor to be music director for the 2020 Ojai Festival, something I have dreamed about since moving to New York twelve years ago. I feel a combination of joy and responsibility to showcase composers and works that create something like an INVISIBLE BRIDGE between the two continents in which I am living and working: Europe and the USA. I have realized that my role as musical communicator – as composer, conductor, educator, and festival di- rector – is to actively strengthen the interactions and connections between the music of today and its heritage in the US and on the “old continent”. As a European living in New York and Paris, I want to explore this INVISIBLE BRIDGE as one of the key elements for my programming of the 2020 Ojai Festival: thoughtful, innovative, loving, provocative, and poetic. Music speaks most directly from hu- man to human, and Ojai is a perfect place to showcase this. I am excited. See you in 2020.” – Matthias Pintscher, 2020 Music Director

Matthias Pintscher is the Music Director of the Ensemble Intercontemporain, the world’s leading contemporary music ensemble founded by Pierre Boulez. In addition to a robust concert season in Paris, he toured extensively with them throughout Europe, Asia, and the United States this season including concerts in Berlin, Brussels, Russia, and the United States. Known equally as one of to-day’s foremost composers, Mr. Pintscher will conduct the premiere of his new work for baritone, chorus, and orchestra, performed by Georg Nigl and the Chorus and Symphonieorchester des Bayer- ischen Rundfunks at their Musica Viva festival in February 2020.

In the 2019/20 season, Mr. Pintscher makes debuts with the symphony orchestras of Montreal, Baltimore, Houston, Pittsburgh, and with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra at Interlochen. He also makes his debut at the Vienna State Opera conducting the premiere of Olga Neuwirth’s new opera Orlando, and returns to the Staatsoper Unter den Linden in Berlin to conduct performances of Beat Furrer’s Violetter Schnee, which he premiered in January 2019. Re-invitations this season include the Cleveland Orchestra, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, and Chamber Orchestra of Europe. In summer 2020, Mr. Pintscher will serve as Music Director of the 74th Ojai Music Festival.